Surviving Biafra: A Nigerwife's Story

London: Hurst Publishing House, 2018

This book showcases a unique account of living in Biafra throughout the Nigerian Civil War. Rosina ("Rose") Martin, a young British woman, met Nigerian John Umelo one cold morning in 1950’s London, eventually marrying him and moving with their three young children to Eastern Nigeria in 1964.

Rose began teaching Latin in Enugu, the region’s capital, and the family enjoyed a quiet, pleasant life, soon welcoming their fourth child. The war broke out in July 1967, and by October, Nigerian Federal troops were poised to take Enugu. Like many others, the Umelo family fled – heading south to John’s ancestral home. From there, they moved from place to place as the war closed in.

Throughout the war, Rose kept notes and started crafting a narrative that captured the day-to-day reality of living in Biafra - from excitement at the beginning to despair at the end. She completed her account soon after the war. She went on to a successful career as a novelist and editor, but her war account was never published, and eventually she loaned the manuscript to the Imperial War Museum in London.

I came across it there, while researching the Asaba Massacre. Rose’s vivid account of life in the East didn’t quite fit that project, but it stuck with me. As the Asaba book neared completion, I returned to it, hoping to finally get her work published. The IWM had no records of where Rose was, but after turning to social media, I discovered she was living in East London, after spending 50 years in Nigeria. We met, and our collaboration was born. I edited and annotated her story, which is the center of this book, framed by my history of the war, with special attention to Britain’s involvement. The book concludes with a brief account of Rose’s post-war life and career, with reflections on Biafra after five decades.

Step by step, as she lived in the villages with her growing family, Rose "became" a Biafran; she planted, harvested, mended, and helped care for the sick and dying. And while the war raged around her, she gave birth in a makeshift camp under a roof of palm-fronds, tended by a traditional midwife and surrounded by her family. Unlike many memoirs written years after the war, her story offers direct insight into experience, without benefit of hindsight; she decided not to revisit the text. As a white foreigner, Rose did not experience the war in the same way as many others, but as she put it, she was indeed one of the millions "living from hope to hope" in those terrible years.

Surviving Biafra can be bought from the publisher, from Amazon (UK and US) and other bookstores, and from Roving Heights bookstore in Nigeria.

For more information about Rosina Umelo and her career as a writer in Nigeria, click here.

Above: A war correspondent took a photo of Rose and her daughter Osondu Elizabeth, born in a makeshift camp in 1968.

Below: Rosina Umelo in 2018

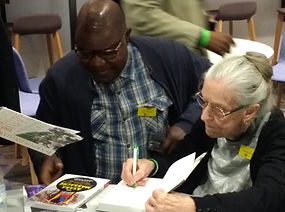

L to R: Rosina Umelo and Liz Bird launch Surviving Biafra in London, at the 2019 Igbo Studies Conference, School of Oriental and African Studies; Rose signs for an admirer, SOAS; Liz Bird launches the book in Nigeria at the Ake Literary Festival, Lagos, 2018

Book Reviews

Times Literary Supplement (TLS)

June 7, 2019

by Sarah Jilani.

In the 1960s, Nigeria was no stranger to “foreign white wives: expensive, unfriendly, infertile and transient”. So writes Rosina Umelo, née Martin, who was decidedly unlike such “Nigerwives” of the time (a “Nigerwife” being a non-Nigerian woman married to a Nigerian man). She and her husband John met in the late 1950s on a London tube platform. By 1965, they were married with three children, and they decided to settle in Enugu, Nigeria. Both working class, the Umelos never socialized in the expatriate world of “the club” (though life as a white English teacher in Enugu still came with colonial advantages). Rose Umelo led “a quiet and contented life with babies and books” until, in 1966, talk of secession and reports of killings began.

Edited and annotated by the anthropologist S. Elizabeth Bird, Surviving Biafra derives from Umelo’s account of living through the three-year war that began after Eastern Nigeria declared itself the independent Republic of Biafra in 1967. Bird contextualizes Umelo’s story with an accessible historical overview, explaining, among other things, how the British colonial strategy of “divide and rule” left Nigeria segregated along ethnic lines, with most of the Muslim Hausa and Fulani in the North; Yoruba in Lagos and the South; and the predominantly Christian Igbo in the East. She also explains how two coups in 1966 led to the killing of 30,000 Igbo in the North, sparking the East’s secession. The well-trained Nigerian Federal Army received arms from Britain, whose leaders wanted to ensure that oil operations in the secessionist East remained under Shell-BP. The Soviets also supported the Federals, fearing a destabilized West Africa. Biafra, outnumbered, was cut off from food and supplies. Images of Biafran children with severe kwashiorkor (a form of protein malnutrition) galvanized some humanitarian action from the West, but also, for some, became synonymous with “Africa”. Hostilities ended in January 1970 with a reunified Nigeria. Two million Biafrans had died.

As a white foreigner, Umelo did not experience the war as her fellow Eastern Nigerians did. She gradually “became” Biafran, however, accepted by her husband’s Igbo community, as everyone helped each other through three years of hardship. Umelo’s harrowing account does not exoticize: she often simply details daily life under extraordinary circumstances: harvesting, mending, care-taking and sometimes fleeing. She captures the reality of living in Biafra – from the early excitement to the bitter end. Surviving Biafra takes its place in a valuable corpus of grassroots accounts of the war that include novels such as Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun(2006) and Buchi Emecheta’s Destination Biafra (1982). Putting ordinary people to the fore, it reminds us that women often pay the greatest price in war.

African Studies Quarterly

Vol 18, October 2019

by Cyril-Mary Pius Olatunji and Mojalefa J.L. Koenane,

Reading Surviving Biafra is in many ways exceptionally thrilling. The text is a combination of history, autobiography, biography and strands of a story including what could be described as semi-fictions to make a new literary genre ... To the greatest possible extent, the authors have composed an objective and apolitical presentation of a Nigerian historical phenomenon.

Rosina Umelo initially took the stance of “an outsider” ... The outsider stance has contributed to making the original compiler acutely aware of mundane things that any local would have taken for granted and that as war dragged on she became fully integrated like any other Biafran experientially (p. 5). The anthropological ingenuity of the blend notwithstanding, the text remains a true first-hand phenomenologically driven record of an eyewitness rather than an intellectual interpretation on the Biafra war. The records were carefully woven into a unique literary genre.

The first of the three parts of the text pictures the pre-Biafran Nigeria, describing the hopes and fears that attended the eve and dawn of the independence. The second part deals with the war especially as it affected Rosina and her family. This was crafted in unique style and language so calm, clear, informative and beautiful in its description of day-to-day living during the war. Like most other popular stories about Biafra, Surviving Biafra also describes the political scandals that attended the newly independent Nigeria, the valor of the Biafra soldiers in spite of the initial paucity of their war arsenal, and the food shortage which created the ugliest scenes. The text refrains however, from making the usual popular claim that the starvation was a deliberate device of the Nigerian government to scuttle Biafra. Nevertheless, it bemoans the colossal destruction of lives, property, and trust among Nigerians and the quagmires that eclipsed the nation in a torrent of lasting instability ....

In spite of their intention to write a reliable and credible story, it seems evident from a few comments in the text that the authors mostly edited the script of a pro-Biafra citizen. Nevertheless, the text builds up a phenomenological challenge to some existing positions in philosophy, anthropology, history, and even beyond, relating to Africa. Some of the most intellectually thought-provoking aspects relate to issues of polygamy, corruption, patrilinealism, cross-racial marriage, and womanhood in Africa.

For full review, click here